|

|

|

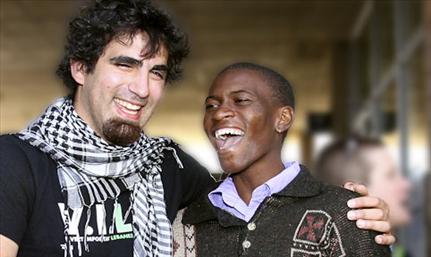

Our SRC presidents: Richard Chemaly (Bloemfontein Campus) and Bongani Ncgaca (Qwaqwa Campus)

Photo: Hannes Pieterse

|

Photo Gallery

The successful and peaceful completion of the University of the Free State’s (UFS) Student Representative (SRC) elections 2011 herals a new dawn for student governance with the announcement of the results today (1 September 2011).

The SRC elections at the Qwaqwa Campus were completed on 25 August 2011, while the elections at our Bloemfontein Campus took place on 29 and 30 August 2011.

“A new dawn heralds a new day when Richard Chemaly, the son of Lebanese immigrants becomes President of an SRC, as elected by students from all racial backgrounds and from across the student body at large. A new day has arrived when candidates could have won voter support across racial lines; a new day is here when all SRC members are now recognised leaders on the basis of academic accountability,” the Dean of Student Affairs, Mr Rudi Buys, says.

A new dawn has arrived; firstly, insofar as student elections for the choice of student leaders at the UFS now proceed according to a non-racial and a non-party political basis.

Not only did the SRC elections at both the Bloemfontein and Qwaqwa Campuses achieve its required quorum, with 31% (4 729 votes) and 50% (2 112 votes) voter turnout, respectively, but the SRC elected by students at the Bloemfontein Campus is 55% black and 45% white, and 60% female and 40% male. The numbers of votes gained by successful candidates also indicate that voters from all racial backgrounds have voted for their candidates of choice.

Secondly, a new dawn has arrived insofar as student governance occupied by only some student groups claiming to speak on behalf of all students has made way for direct voting for candidates by the broad student body and the threefold increase of student governance structures on campus.

Not only did all students at our Bloemfontein and Qwaqwa Campuses (a total of 15 173 and 4 257, respectively) have the opportunity to participate in voting directly, but nine additional Student Councils were established at our Bloemfontein Campus that each holds an ex officio seat on the SRC and allows for student governance in all the major student sectors of the student body, such as for postgraduate students, international students and all categories of student associations.

The various councils now established include the Student Academic Affairs Council, the Student Associations Council, the Postgraduate Student Council, the International Student Council, the Student Media Council, the Residences Student Council, the Commuter Student Council and the Rag Community Service Fundraising and Service Councils. In addition, all faculties also introduced student representative structures at departmental and faculty level in 2011 to ensure student participation in faculty management and governance.

The SRC members at the Bloemfontein Campus are:

Elective portfolios:

President: Mr Richard Chemaly

Vice-President: Mr Lefata David Maklein

Secretary: Ms Matshepo Ramokgadi

Treasurer: Mr Werner Pretorius

Arts & Culture: Ms Alta Grobelaar

Accessibility & Student Support: Mr William Clayton

First-generation Students: Ms Petre du Plessis

Media, Marketing & Liaison: Ms Biejanka Calitz

Sport: Mr Bonolo Thebe

Student Development & Environmental Affairs: Ms Busisiwe Madikizela

Transformation: Ms Qaqamba Mhlauli

Ex officio portfolios:

Dialogue & Ex officio: Associations Student Council: Mr Anesu Ruswa

Academic Affairs & Ex officio: Academic Affairs Student Council: Mr Jean Vermaas

Residence Affairs & Ex officio: Campus Residences Student Council: Ms Mpho Mokaleng

City student Affairs & Ex officio: Commuter Student Council: Ms Annemieke Plekker

Postgraduate Affairs & Ex officio: Postgraduate Student Council: Ms Glancina Mokone

International Affairs & Ex officio: International Student Council: Mr Pitso Ramokoatsi

Student Media Affairs & Ex officio: Student Media Council: Ms Nicole Heyns

RAG Community Service & Ex officio: RAG Fundraising Council: Ms Iselma Parker

RAG Community Service & Ex officio: RAG Community Service Council: Ms Motheo Pooe

In the Qwaqwa elections, SASCO achieved 36,84% of the vote, with SADESMO, PASMA and NASMO each achieving 29,73% and 18,56% and 12,74%, respectively .

Mr Bongani Ncgaca was elected as the President of the SRC at our Qwaqwa Campus, while the names of the SRC members at the campus will be announced on 7 September 2011.

The Central SRC will be established on 8 September 2011 by a joint sitting of the two SRCs.

The successful completion of the SRC elections at the Bloemfontein Campus follows a yearlong review process of student governance by a Broad Student Transformation Forum (BSTF) that consists of 59 delegations from student organisations and residences. The BSTF adopted independent candidacy for elective portfolios and additional student councils to provide ex officio seats on the SRC as the template for student governance, following the consideration of a series of benchmarking reports on student governance nationally and internationally.

The UFS Council adopted the new SRC Constitution, as drafted and submitted by the BSTF, on 3 June 2011.

Media Release

1 September 2011

Issued by: Lacea Loader

Director: Strategic Communication

Tel: 051 401 2584

Cell: 083 645 2454

E-mail: news@ufs.ac.za